What is the Vulvar Vestibule?

A Closer Look at an Overlooked Structure in Women’s Health

Burning, stinging, or soreness at the vaginal opening - especially with touch, sitting, wiping, or intimacy - is more common than many realize. These symptoms are often linked to a small but powerful part of your anatomy called the vulvar vestibule.

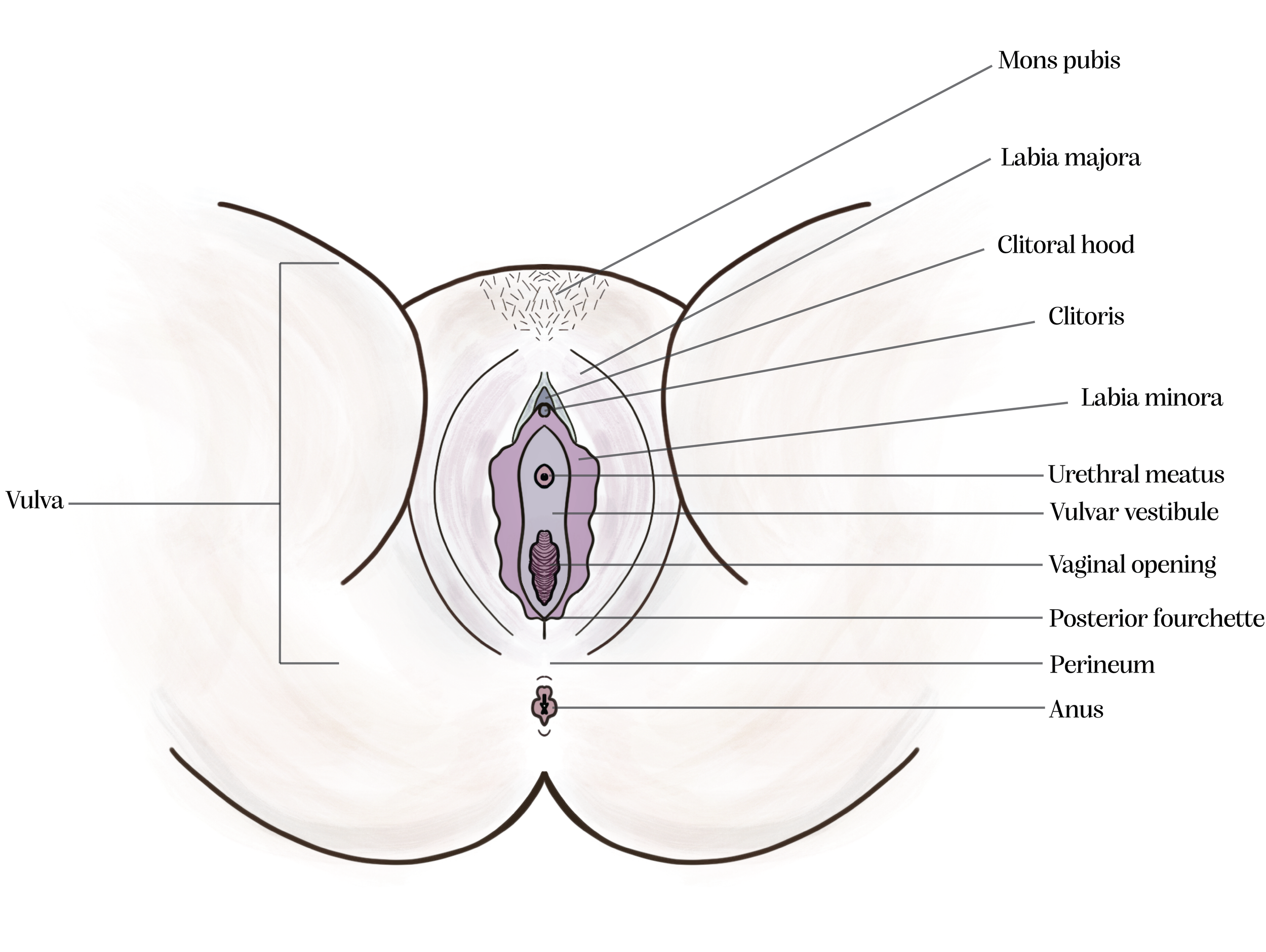

The vulvar vestibule is a small area located around the entrance to the vagina and urethra (where urine exits the body), within the external female genitalia known as the vulva. It forms a zone bordered on the top by the clitoris, on the sides by the inner lips (labia minora), and at the bottom by the posterior fourchette - a thin fold of tissue where the labia minora meet.

This region contains Bartholin glands, Skene glands, and minor vestibular glands. It also houses dense nerve endings and hormone-sensitive tissue, making it highly responsive and particularly vulnerable to pain conditions such as vestibulodynia.

Recent research has highlighted the vestibule’s unique anatomy, developmental origins, immune function, and hormonal responsiveness - shedding light on why this small structure can be a significant source of discomfort for many.

This diagram highlights the key landmarks of the vulva, including the vulvar vestibule which lies within the inner border of the labia minora, surrounding the urethral and vaginal openings.

Key Structures Within the Vestibule

The vestibule is outlined by Hart’s line - a subtle boundary marking the transition between the soft vestibular mucosa and the slightly tougher, more skin-like surface of the labia minora.

The vestibule includes:

Vaginal Opening: The entrance to the vagina, located centrally within the vestibule.

Urethral Meatus: The opening through which urine exits the body, located just above the vaginal opening.

Bartholin’s Glands: Mucus-secreting glands that help lubricate the vaginal opening during sexual arousal, reducing friction and enhancing comfort. The glands themselves sit beneath the vestibular surface, with their ducts open at the 5 and 7 o’clock positions.

Skene’s Glands (also called Paraurethral Glands): Small glands that help maintain moisture and protect against bacteria around the urethra. These sit deep to the vestibular surface, with duct openings at the 11 and 1 o’clock positions.

Minor Vestibular Glands: Tiny, mucus-producing glands scattered throughout the vestibular lining. They help keep the tissue moist and protected from irritation, especially during everyday activities.

Vestibular Bulbs: While not part of the vestibule itself, these paired erectile tissue structures lie just beneath the vestibular skin. They are part of the clitoral complex and during sexual arousal, they fill with blood to enhance pressure, sensation, and fullness in the surrounding tissue.

This diagram illustrates Hart’s line and highlights the anatomical locations of the Bartholin glands and Skene glands, using the vulvar clock as a reference point for orientation.

How The Vestibule Develops - and Why It Matters

The vulvar vestibule develops from a layer of tissue called the endoderm, one of the earliest layers formed during embryonic development (the process by which a fertilized egg grows and forms the foundational structures of the body). The endoderm also forms the inner linings of organs like the bladder, intestines, and urethra. This sets the vestibule apart from nearby tissues: the vagina develops from the mesoderm (a layer that forms muscles, bones, and connective tissues), while the outer vulva develops from the ectoderm, the layer that becomes skin and the nervous system.

Because of its unique origin and tissue type, the vestibule behaves differently than the tissues around it. It is lined with non-keratinized mucosal epithelium—a soft, thin type of tissue similar to the inside of the mouth. Unlike skin, this tissue lacks a protective outer layer called keratin, making it more vulnerable to friction, dryness, and irritation. As a result, the vestibule tends to be more sensitive to hormones, more reactive to inflammation, and more prone to pain even from light touch. It also contains a rich supply of nerve endings, which contributes to its heightened sensitivity.

This distinct developmental background helps explain why the vestibule is often a key site of discomfort in conditions like vestibulodynia.

Why the Vestibule Matters in Pain Conditions

The vestibule plays a unique role in pain conditions like vestibulodynia due to its distinct nerve structure and embryological origins.

Some individuals are born with neural hypersensitivity in the vulvar vestibule - meaning their nerve endings may be naturally more sensitive or more densely concentrated. This is known as primary neuroproliferative vestibulodynia. Interestingly, individuals with this condition often report increased sensitivity in their belly button which may be due to shared embryologic origins and similar patterns of nerve development.

The vestibule develops from the urogenital sinus, a structure that forms early in embryonic development from the endoderm (the same tissue layer the vestibule comes from). Other tissues with this same origin include the urethra, urinary bladder, Skene’s glands, and Bartholin’s glands, which may also exhibit heightened sensitivity or reactivity in some individuals.

Others may develop hypersensitivity later in life - this is known as acquired neuroproliferative vestibulodynia and may be triggered by chronic inflammation, repeated infections, or hormonal changes. These factors can stimulate excessive nerve growth in the vestibular tissue, leading to localized hypersensitivity.

Recognizing these underlying mechanisms helps validate the real, physical nature of pain experienced in vestibulodynia and underscores why specialized care is essential.

How Inflammation Affects the Vestibule

Inflammation is believed to play a major role in the development of vestibular pain. One theory, called neurogenic inflammation, suggests that repeated irritation or infection in the vestibule can cause pain-sensing nerve fibers to grow excessively, change how pain receptors work, and release chemicals that keep the tissue inflamed. This cycle can make the vestibule more reactive over time.

Many individuals with vestibulodynia report a history of frequent yeast infections before their symptoms began. Research shows that cells from the vestibule respond more strongly to irritants than cells from other parts of the vulva. But in those with vestibulodynia, this response is even more intense and esaggerated - suggesting that the vestibule is a highly sensitive tissue that can overreact to minor triggers, even if there’s no visible infection present. In these cases, the inflammation can continue long after the original cause is gone, contributing to ongoing discomfort.

Hormonal Influences on the Vestibule

The vestibule is also very sensitive to changes in hormone levels—especially estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. Estrogen plays a key role in keeping the tissue thick, elastic, and well-lubricated. When estrogen levels drop—such as during menopause, while breastfeeding, or after stopping hormonal birth control—the vestibular tissue can become thinner, drier, and more fragile. This often leads to discomfort, burning, or pain with touch or penetration.

Hormonal birth control can also lower natural estrogen and testosterone levels, which may increase sensitivity in some individuals. Research suggests that vestibular tissue may respond differently than vaginal tissue to hormone levels - meaning it’s possible to have a well-estrogenized vagina and still experience discomfort or atrophy in the vestibule. In these cases, applying low-dose estrogen (or a combination of estrogen and testosterone) directly to the vestibule may help improve symptoms.

Testosterone also plays a role in tissue healing, lubrication, and nerve sensitivity. Some individuals may have a genetic difference that makes their body’s testosterone receptors less effective. When combined with hormonal changes—such as starting birth control—this may increase the risk of developing vestibular pain. Ongoing research is exploring how both hormone levels and individual differences in hormone response affect pain in the vestibule.

You’re Not Alone - And Your Pain is Valid

The vulvar vestibule may be a small area, but it plays a big role in physical comfort, sexual function, and overall well-being. Persistent symptoms like vaginal entrance pain, burning, or tenderness that disrupt daily life or relationships are not uncommon—and they are not imagined. Increased awareness of the vestibule’s anatomy, function, and vulnerability to pain offers an empowering starting point. With evidence-based treatment, education, and pelvic floor physical therapy, meaningful relief is possible—and deserved.

If symptoms persist, it’s important to seek care from a vulvar specialist - someone experienced in diagnosing and treating vestibular pain - so that healing isn’t delayed and the right support can begin.

References:

Lev-Sagie, A., Gilad, R., & Prus, D. (2019). The Vulvar Vestibule, a Small Tissue with a Central Position: Anatomy, Embryology, Pain Mechanisms, and Hormonal Associations. Current Sexual Health Reports, 11, 60–66.

Note:

This blog is for informational purposes only and does not provide medical advice. It is not intended to diagnose or treat any medical condition. Please consult your healthcare provider before making decisions about your health or treatment options.